Government officials and economists the world over have had great difficulty, especially in developed countries, in stimulating job growth to a material degree in their respective economies, ever since the millennium crossover. Productivity has continued its steady rise up the scale, but according to most economics textbooks, these gains are supposed to lead to more jobs, higher wages, and greater wealth accumulation, but such has not been the case for a disturbingly lengthy period of time.

Most experts point to technology and its incumbent innovation and change as the drivers of productivity increases, but most attribute benefits from these investments in the long run. Yes, there will be disruption as workers are displaced and must acquire new skills, but there appears to be dark side that no one had anticipated, nor accounted for in the scheme of things.

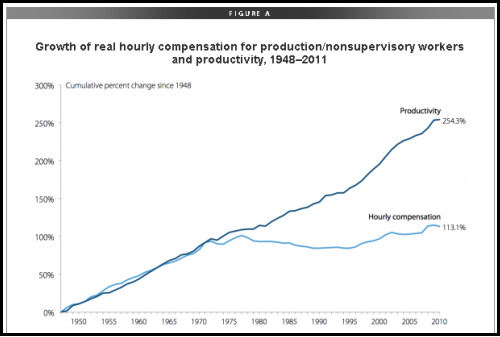

The story of productivity gains since World War II has always been touted as the poster child for investments in new technology. Presented below is a representative chart for the United States for the period:

The hourly compensation of production workers tracked very closely with gains in productivity until the late seventies. The two lines then diverged with the wage-related line remaining flat for four decades. Automation, coupled with the massive offshoring of jobs to lower-labor cost markets, has often been cited as the true cause, but the onset of far reaching globalization strategies in response to local competitive pricing pressures should also receive some of the credit.

Politicians and labor advocates have focused on these elements that are self evident if one only reviews the published annual reports of the IMF. The most sobering chart of the group presents GDP growth over this same period of time for developed versus developing countries. There is a highly visible “X” on the chart as the line for developed markets declines down to 2%, while the line for developing markets ascends, unabated, to the 7% region. The divergence began in 1990 when China’s economy roared into gear, as did India’s to a lesser degree.

But what about job growth and productivity gains?

After reviewing these charts, it is easy to conclude that the scourges of outsourcing are to blame for dismal job growth and the flattening of earned income. This conclusion, however, is only partially correct. It was not that long ago that management structures resembled pyramids in shape, but the information age has eliminated the need for minions of management supporters. Organizations today are more flat as a consequence. Instead of three direct reports, there may be as many as ten.

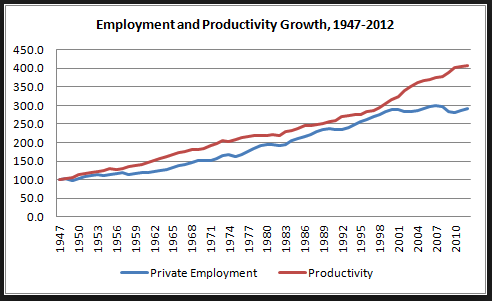

The following chart depicts the current conundrum:

From 1970 until 2000, the new jobs added were mostly lower paying, leading to the flat hourly compensation behavior in the previous graph. The disturbing divergence occurs here in 2000. Erik Brynjolfsson, a professor at the MIT Sloan School of Management, and his collaborator and coauthor Andrew McAfee have been arguing that rapid technological change has been destroying jobs faster over the last 10 to 15 years than it has been creating them.

Their contention may threaten the faith economist have in technological progress. Brynjolfsson points out, “Productivity is at record levels, innovation has never been faster, and yet at the same time, we have a falling median income and we have fewer jobs. People are falling behind because technology is advancing so fast and our skills and organizations aren’t keeping up.”

Lawrence Katz, a Harvard economist, does not dismiss that today’s digital technologies are different. Labor markets may adapt over time, but “If technology disrupts enough, who knows what will happen?”

Forextraders.com provides current data revolving around the economy and in-depth education for the foreign exchange market.